HOME HOME  ARTICLES ARTICLES  BIBLES BIBLES  LINKS LINKS  HERETIC HERETIC

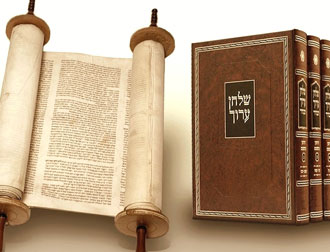

About the Talmud, Mishnah, Gemara, Torah She’b’al Peh, and Halakhah About the Talmud, Mishnah, Gemara, Torah She’b’al Peh, and Halakhah

What Is the Talmud?

An intergenerational rabbinic conversation that is studied, not read.

Talmud : (literally, “study”) is the generic term for the documents that comment and expand upon the Mishnah (“repeating”), the first work of rabbinic law, published around the year 200 CE by Rabbi Judah the Patriarch in the land of Israel.

Although Talmud is largely about law, it should not be confused with either codes of law or with a commentary on the legal sections of the Torah. Due to its spare and laconic style, the Talmud is studied, not read. The difficulty of the intergenerational text has necessitated and fostered the development of an institutional and communal structure that supported the learning of Talmud and the establishment of special schools where each generation is apprenticed into its study by the previous generation.

The Mishnah

In the second century, Rabbi Judah the Patriarch published a document in six primary sections, or orders, dealing with agriculture, sacred times, women and personal status, damages, holy things, and purity laws. By carefully laying out different opinions concerning Jewish law, the Mishnah presents itself more as a case book of law. While the Mishnah preserved the teachings of earlier rabbis, it also shows the signs of a unified editing. Part of that editing process included selecting materials; many of the traditions that did not “make it” into the Mishnah were collected in a companion volume called the Tosefta (appendix, or supplement).

The Mishnah defined the basic contours for later discussion of Jewish law. The name, which means “repeating,” reflects that the book was designed for oral transmission and memorization, as a rabbi would repeat each tradition for his student. But the orality of the Mishnah is not just a matter of its form; the content is composed almost entirely of the statements of different rabbis, juxtaposed against and in conversation with the varying opinions of other rabbis. From the Mishnah onward, all of the literature of the Torah she’b’al peh is more than just “oral Torah”; in fact, a more descriptive translation of the term might be “conversational Torah,” because it is the conversation and the interaction of different ideas that defines the essence of what eventually became known as the Talmud(study).

The Gemara (“learning”)

After the publication of the Mishnah, the sages of Israel, both in the land of Israel, and in the largest diaspora community of Babylonia (modern day Iraq), began to study the both the Mishnah and the traditional teachings. Their work consisted largely of working out the Mishnah’s inner logic, trying to extract legal principles from the specific statements of case law, searching out the derivations of the legal statements from Scripture, and relating statements found in the Mishnah to traditions that were left out. Each community produced its own Gemara which have been preserved as two different multi-volume sets: the Talmud Yerushalmi includes the Mishnah and the Gemara produced by the sages of the Land of Israel, and the Talmud Bavli includes the Mishnah and the Gemara of the Babylonian Jewish sages.

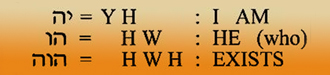

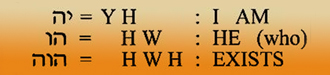

Torah She’b’al Peh, or Oral Torah

Nevertheless, Jews sought to determine from the Torah all of the details of a complete legal system. As tradition describes it, from the time of the very giving of the written Torah, Moses already had received a companion Torah she’b’al peh (oral Torah), which he proceeded to teach to the people of Israel during their travels in the desert. It is clear that from the very beginning, Jews needed additional authoritative law, or halakhah (“going,” or “path”), to govern regular life. These halakhot (plural) were passed on through the generations, and during the period of the Second Temple (fifth century BCE-first century C.E.), halakhot, both those developed through custom and those derived from interpretation of the Torah, were collected and transmitted. Following the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., the earliest rabbis gathered and transmitted the laws learned from earlier sages. During the first two centuries, the rabbis apparently worked out how, as an educated leadership, they were to transmit and develop new law through agreed upon rules of interpretation. Much of our understanding of this period comes from later texts which were not intended as histories and which probably should not be relied upon for history.

Nevertheless, it is clear that by the close of the second century, the rabbis had agreed on enough of the basics that their various opinions could be compiled and compared to each other. At this point, around the year 200 C.E., Rabbi Judah the Patriarch, used his unique position as a leader of the Jewish people who actually got along with the Romans to publish the first major Jewish work following the Bible, a study book of rabbinic law called the Mishnah (literally, teaching or repeating).

Halakhah: The Laws of Jewish Life

Halakhah is the "way" a Jew is directed to behave, encompassing civil, criminal and religious law. The root of the Hebrew term used to refer to Jewish law, halakhah, means “go” or “walk.” Halakhah, then, is the “way” a Jew is directed to behave in every aspect of life, encompassing civil, criminal and religious law. The foundation of Judaism is the Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, sometimes referred to as “the Five Books of Moses”). “Torah” means “instruction” or “teaching,” and like all teaching it requires interpretation and application. Jewish tradition teaches that Moses received the Torah from God at Mount Sinai. The Torah is replete with instructions, directives, statutes, laws, and rules. Most are directed to the Israelites, some to all humanity.

Halakhah comes from three sources: from the Torah, from laws instituted by the rabbis and from long-standing customs. Halakhah from any of these sources can be referred to as a mitzvah (מִצְוָה, commandment; plural: mitzvot מִצְוֹת). The word "mitzvah" is also commonly used in a casual way to refer to any good deed. Because of this imprecise usage, sophisticated halakhic discussions are careful to identify mitzvot as being mitzvot d'oraita (an Aramaic word meaning "from the Torah") or mitzvot d'rabbanan (Aramaic for "from the rabbis"). A mitzvah that arises from custom is referred to as a minhag. Mitzvot from all three of these sources are binding, though there are differences in the way they are applied.

Return to top

HOME HOME  ARTICLES ARTICLES  BIBLES BIBLES  LINKS LINKS  HERETIC HERETIC

|

|