~ from article by Christine Egbert. Quartodeciman Controversy 155 AD Consequently, during this period Roman Christians, who had never set foot in a synagogue or studied what they called the Old Testament, were unaware that the Almighty had strictly forbidden the name of a pagan deity ever crossing their lips (Exodus 23:13). So, in their ignorance, the Roman church began to call the day following the weekly Sabbath during First Fruits by the name of the pagan sun-goddess, Ishtar, which in English is pronounced Easter. Between the churches of Asia Minor in the east and those of Rome in the west, Easter became a divisive issue. Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna, who had been discipled by the apostle John himself, argued for continuing to observe the Messiah’s death on Passover, the 14th of Nisan, the Feast of Unleavened Bread on the 15th, and Jesus’ (Yeshua’s) resurrection on the day following the weekly Sabbath (during the Passover week), a day known in Scripture as First Fruits. This was the way Jesus (Yeshua) had taught the apostle John, and John had taught Polycarp. And it was the way the 1st Century church had always commemorated the event. [Resurrection day was not on a Sunday - see article: The Crucifixion - 3 Days and 3 Nights.(under construction)]. The Bishop of Rome, Anicetus, saw it differently. Wanting to distance himself from those Jews, he insisted the entire church (east and west) should commemorate the resurrection the way they did it in Rome (from whence, I am certain, came the motto: “When in Rome, do as the Romans”). They Agree to Disagree The Bishop of Ephesus

Versus

The Bishop of Rome “There was a considerable discussion raised about this time, in consequence of a difference of opinion respecting the observance of the paschal [Passover] season. The churches of all Asia, guided by a remoter (an older) tradition supposed that they ought to keep the fourteenth day of the moon (Nisan) for the festival of the Savior’s passover, in which day Jews were commanded to kill the paschal lamb … The bishops of Asia, who persevered in observing this custom handed down to them from their fathers, were headed up by Polycrates, who indeed, had also set forth the tradition handed down to them, in a letter which he addressed to Victor and the church of Rome. ‘We,’ said he, ‘therefore, observe the genuine day; neither adding there to nor taking there from. For in Asia great lights have fallen asleep, which shall rise again the day of the Lord’s appearing, in which He will come with glory from heaven, and will raise up all the saints …Moreover, John, who rested upon the bosom of our Lord, and also Polycarp of Smyrna, both bishop and martyr . . . Thraseas, … Sagaris, … Papirius, and Melito … All these observed the fourteenth day of the Passover according to the gospel, deviating in no respect, but following the rule of faith. Moreover, I, Polycrates, who am the least of all of you, according to the tradition of my relatives, some of whom I have followed. For there were seven of my relatives [who were] bishops, and I am the eighth; and my relatives always observed the Day when the people (i.e., the Jews) threw away the leaven.” Victor, the Bishop of Rome, sought to excommunicate Polycrates and all Christians who dared to hold fast to the biblically commanded observance of the 14th of Nisan. But after Irenaeus and some others interceded on Polycrats behalf, Victor finally relented. But make no mistake, Polycrates’ letter proves that the Churches of Asia Minor never accepted Rome’s authority.

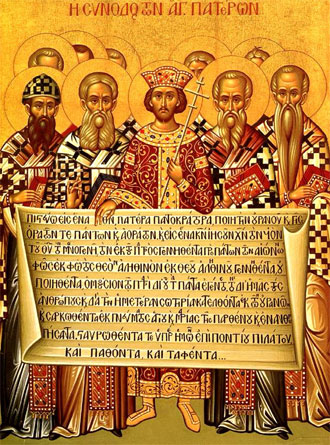

Rome Enforces Easter / Outlaws Passover During the council of Nicaea, in which no Jewish believers were allowed to participate, many topics were dealt with. Many disputes were resolved with good outcomes. But that Council’s decision regarding Passover and Easter began a process finalized a few decades later at the Council of Laodicea, which severed mainstream Christianity from its Hebraic roots. That separation, along with the Roman Catholic Church’s self-proclaimed right to “add to and take away” from Scripture, to redefine the established orthodoxy taught by Yeshua to his apostles, launched the world into what historians call the Dark Ages. Urged by the Christians of Alexandria, the Roman Emperor Constantine at the Council of Nicaea ruled that Easter, which up to then had been observed on the Sunday following the weekly Sabbath, during the Feast of Unleavened bread (First Fruits), was to be celebrated, by all churches, on the first Sunday after the spring equinox (the day on which Ishtar, the sun-goddess, was said to have landed in the Euphrates in a giant Ishtar-egg), regardless of when the Jewish (biblical) Passover fell. And Christians, from then on, were forbidden by Rome to observe Passover or to have any fellowship with those “detestable Jews”. To celebrate this new State-Church ruling, Constantine waged a vile anti-Semitic attack against all 14th (Quartodeciman) proponents, ordering the severest of punishments (death) on those who failed to comply. But in spite of this, it was several centuries before Rome’s edict became a standard throughout Christendom. |

|

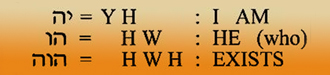

ברוך אתה יי אלוהינו מלך העולם Blessed are You O YAHWEH our ELOHIM, King of the Universe |

|